The Arian Controversy

Alexander, Bishop at Alexandria, maintained the

Orthodox position of the church against the Arians. That the Son is de facto

co-eternal with the Father. As all scientific theories must show themselves

falsifiable to qualify as theories, so too does Athanasius provide a test of

falsifiability with his claim that, “…our adversaries must first prove that the

Son is not the Son, but a creature made of nothing. Then, when they have done

this, they may clamour as they like of His not being before He began to exist.

In a

letter composed by Arius to Eusebius he states, “To the most desired Master,

the faithful man of God, the Orthodox Eusebius, Arius, who is unjustly

persecuted by Father Alexander, on account of the truth which conquereth all

things, which truth thou also shieldeth…For the Bishop wastes and persecutes us

exceedingly, and sets in motion every evil against us; so that he has driven us

out of the city as godless men, because we do not agree with his assertion made

in the public that God always existed [and that], the Son always existed, [and]

that the Son has existed as long as the Father has, that the Son has [always]

co-existed uncreatedly with God…”.

Chrystal, James. 1891. Authoritative Christianity. Vol. 1 pp. 178-9

Arius was a student at Antioch before becoming Presbyter of the church

at Alexandria, Egypt. In ca. 318 A.D. Arius entered into a contentious

disagreement with the then Bishop of Alexandria, Alexander, regarding the

essence and eternality of the Son. Alexander defended the Orthodox position

that the Son existed co-eternally with the Father, as such, His divinity would

be axiomatic disqualifying Him as a creature. Arius believed that to say the

Son was divine would be heresy, as such a belief would imply a polytheism. By

contrast, Arius contended that the Son was a created being, created by God the

Father, who subsequently created all other beings. Alexander believed that such

a view would deny the deity of Christ which is supported by both scripture and

by the common practice of the church in its worship. For such a view Arius was

deposed and excommunicated, however, he was popular with many of the people,

and enlisted the aid of certain Bishops. In 324 A.D. Hosius, Bishop of Cordova,

brought with him a letter from the emperor Constantine, urging Alexander and

Arius to make amends. Hosius’ report back to Constantine strongly favored the

position of Alexander while discrediting the views of Arius. Nevertheless,

Hosius, it was thought, made the recommendation to Constantine that a council

of Bishops should be called to address the matter. However, that point is

contested by some church historians who report that Constantine claimed he had

seen a vision instructing him to call a council together to discuss the matter.

It should be noted, however, that Constantine cared little about the unity of

the Trinity and more about the unity of his empire.

The

council of Nicaea was convened on May 20th 325 A.D. with a disputable number of

318 attendees. Many matters were discussed at the council, but chief among them

was the Arian controversy. As Arius was only a Presbyter (elder) he was not

permitted to sit in on the council. Therefore, Eusebius, Bishop of Nicomedia,

represented Arius at the council. Only a small number represented either side

of the argument with the vast majority lamenting the whole issue that they felt

could divide the church. The party then which rallied round Alexander in formal

opposition to the Arians may be put down at over thirty. Between the convinced

Arians and their reasoned opponents lay the great mass of the bishops, two

hundred and more, nearly all from Syria and Asia Minor. Of all the Bishops who

attended the council, the Arians could only rely on seventeen members who would

support their cause.

What

changed for the conservative majority had to do with Eusebius’ defense of Arius

and of Arianism. Upon hearing the argument of Eusebius, the council went into

an uproar calling him a “blasphemer” and a “heretic.” To counter it, the

council determined to enact a creed clarifying, in the strongest terms, the

orthodox view of the church on the matter. The Creed of Nicaea read in part, We

believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible;

and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of his Father,

of the substance of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very

God, begotten (γεννηθέντα), not made, being of one substance (ὁμοούσιον,

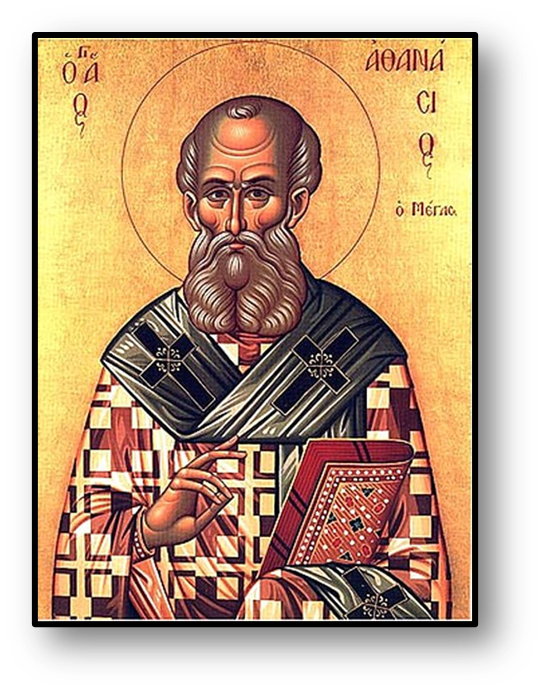

consubstantialem) with the Father. At the time, Athanasius held the office of

Deacon but would later become Bishop and take up the fight of Alexander, after

his passing, against the Arians and defending Nicaean orthodox doctrine.

The

particular issue centered around the Arian motto “there was when He was not”

referring to the Son. Athanasius

observed, as others also did, that Arius declined to include the noun “time” in

his argument. “Why do you not speak out plainly, when you are speaking of time,

and say, ‘There was a time when the Word was not’? No doubt the word ‘time’ is

carefully avoided because you are afraid of alarming the minds of simple folk.

But your meaning and opinion are too evident to be disguised or concealed. For

time is really what you mean when you omit the word, and only say, ‘There was

when,’ instead of ‘There was a time when He was not;’ and ‘He was not before He

was begotten,’ instead of ‘before the time when He was begotten.’” Gregory of

Nazianzus also addressed this same issue by contending that the Father and the

Son are equally eternal in existence. How could the Son be the creator of time

and also be subject to it? The Arians

held that, as He is a created being He would have to be subject to time just as

we are.

Furthermore, because those who are begotten into this world once did not

exist, there must have been a point when the Son also did not exist. But

Gregory argued that to make such a claim was to argue different realities. What

the Arians were essentially doing was confusing contingent being with necessary

being. Most things which exist do so contingently, that is, their existence is

predicated on the existence of something or someone else. In other words, it is

possible for them to not exist. Those things which exist necessarily have their

existence in and of themselves, in other words, it is impossible for them not

to exist. Shapes and numbers are said to exist necessarily, but shapes and

numbers do not create anything. God the Father is said to exist in this

fashion, necessarily, as does the Son. Therefore, the Son cannot be subject to

time, and at the same time be ruler over it. Such a notion would violate the

law of non-contradiction which states that you cannot not have A, and yet have

A in the same sense to the same extent. The generation of the Son is not like

that of a man, which requires an existence after that of the Father, but the

Son of God must, as such, have been begotten of the Father from all eternity.

As regards man’s nature it is impossible, as his nature is finite, but that his

generation should be in time; but the nature of the Son of God, being infinite

and eternal, His generation must, of necessity, be infinite and eternal too.

Arius was employed as Professor of Exegesis, his contention that the Son

was created was based on his exegetical work of scripture. He appealed to such

passages as, Proverbs 8:22; Acts 2:36; Mark 13:32; John 14:28, 17:3; Colossians

1:15 et al, in support of his view. Arius fled to an erroneous LXX rendering of

Proverbs 8:22a and placed these words into Christ’s mouth, “The Lord made

(κτίζω) me….” Athanasius himself accepted

the same Greek word and even applied it to Christ, but he took it in the sense

of an appointing to a position. To him the verse is a declaration that the

Father had “made” His Son the Head over all creation. Beale argues that the

Hebrew word, קָנָה qânâ, means “possessed,” not “created.” In actuality, how the word is translated is

based on the context of the verse. If

the context suggests the constructing of some- thing, then “made” would be

appropriate. If the context suggests something positional, such as proper

ownership, appointment, or the establishment of some-thing, then “possessed”

would be appropriate.

To

counter Arius, the Orthodox church appealed to such verses as, John 1:1; 1

Corinthians 2:8; Philippians 2:6; Hebrews 1:3, 13:8 et al. Regarding John 1:1,

the verb “was”, not ‘came into existence,’ but was already in existence before

the creation of the world. The generation of the Word or Son of God is thus

thrown back into eternity. Thus, Paul calls Him (Col. 1:15) ‘the firstborn of every

creature,’ or (more accurately translated) ‘begotten before all creation,’ like

‘begotten before all worlds’ in the Nicene creed. Comp. Heb. 1:8, 7:3; Rev.

1:8. On these passages is based the doctrine of the Eternal Generation of the

Son. John says distinctly that the Son or Word was existing before time began,

i.e. from all eternity. Furthermore, the verb eimi is a first-person singular

which has been translated as “was,” though it actually means “be”, or “to be”

as in “to exist”. Some translators have claimed that this verb is actually

third person. In the Greek, the verb is in the present tense (Lit. “be”), and in

the emphatic it is most frequently translated as “I Am” or “I exist.” “I” is a

personal pronoun utilized as a first-person singular. Whether first person or

third, the verb itself remains unchanged, it merely determines how the

statement itself should be understood. So, although archē (beginning)

can refer to time in this passage, it is actually utilized in reference to a

person, “In the beginning,” “I Am”.

The

case ending, in the Greek, helps us to determine what the subject or the object

is in relation to the verb. The verb ἦν (“be” or “to be”) appears three

times in this passage and has been translated as “was.” In English, the tense

of the verb is past, but in the Greek the verb is always present tense.

Regardless of whether ἦν is past or present tense, it still exists as a

verb. Because the case ending of λόγος is nominative, this would

indicate that the “word” is the subject while the case ending of θεόν is

accusative, indicating that “God” is the direct object. The preposition πρὸς,

translated “with” is a term of proximity. Literally understood as the Word

being “toward” or “face to face” with God. The preposition qualifies the verb

“was” (lit. “to be”) indicating that God the Son (ὁ λόγος) is “face to face”

with God (πρὸς θεόν) the Father at the beginning (Ἐν ἀρχῇ).

Finally, various terms have been utilized by Historians and Theologians

alike on this subject. Hypostasis (or Hypostatic Union), Consubstantiality,

Homousius, and Homoiousius. One iota really does make all the

difference. The Council at Nicaea settled on the term Homousius (“of the

same nature”) to define their view on the essence of the Son to the Father. While

the Arians preferred the term Homoiousius (“of a similar nature”). The

difference in the spelling comes down to one letter in the Greek, the iota.

Athanasius commented on what the word Homousius was intended to entail,

“That the Son is not only like to the Father, but that, as his image, he is the

same as the Father; that he is of the Father; and that the resemblance of the

Son to the Father, and his immutability, are different from ours… his generation

is different from that of human nature; that the Son is not only like to the

Father, but inseparable from the substance of the Father, that he and the

Father are one and the same”. This word, it was believed, was the best suited

to confute the Arian heresy.

The

term “hypostasis” referred to the Son being of one “substance”, “nature” or

“essence” with the Father. “Hypostatic Union” argued that in Christ He

possessed two natures in one person, His humanity and His divinity making Him

fully human, to pay the penalty for sin, and fully God to become the perfect

sacrifice for sin, without mixture or confusion. The term “consubstantial” was

an older term and was associated with the two previous, and which simply

indicated that Jesus Christ is of the same nature as the Father, essentially

the same as Homousius. In

conclusion, the two-word phrase “eternal generation” was derived from two

words, “begotten” and “monogenes.”

Begotten, comes from the word gennao and means “to be born or

conceived.” The word monogenes

comes from two words, mono meaning “one” or “only” and genos meaning, “one of a

kind” or “unique.” As such, monogenes

consistently denotes “uniqueness,” even in post-apostolic literature. This same

word (monogenes) occurs five times in scripture, and all in John’s gospel. Many

conservative scholars believe that this word depicts the idea of “one and only”

and nothing else and is more prevalent in newer translations. This would

indicate that the church today recognizes what the church councils laid down

several centuries ago, that the Son is eternal in existence, one in nature with

the Father, fully human and fully divine.

Athanasius of

Alexandria, The Orations of S. Athanasius against the Arians. London: Griffith,

Farran, Okeden, & Welsh, 1893

Beale, David.

Historical Theology In-Depth, Vol. 1: Themes and Contexts of Doctrinal

Development since the First Century. Greenville, South Carolina: Bob Jones

University Press, 2013

Percival, Henry R.

Excursus on the Word Homousios in The Seven Ecumenical Councils, edited by

Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, vol. 14, A Select Library of the Nicene and

Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons, 1900

Plummer, A. The

Gospel according to St John, with Maps, Notes and Introduction, The Cambridge

Bible for Schools and Colleges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1902

Robertson, Archibald

T. Prolegomena, in St. Athanasius: Select Works and Letters. Edited by Philip

Schaff and Henry Wace, vol. 4, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene

Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. New York: Christian Literature

Company. 1892

Philip Schaff and

Henry Wace, eds., The Nicene Creed, in The Seven Ecumenical Councils.

Translated by Henry R. Percival, vol. 14, A Select Library of the Nicene and

Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series. New York: Charles

Scribner’s Sons. 1900

Comments

Post a Comment